Deep in the Russian tundra, where woolly mammoths used to roam and temperatures reach -50°C, an eccentric Russian scientist has been studying the Arctic’s permafrost for the last 40 years. Sergei Zimov moved to the edge of Russia, namely Chersky, with his wife Galina in 1980. Chersky is located on the banks of the Kolyma river, further East than Japan, and further north than Iceland, its location was suitable for Gulags—and not much else.

Bisons at the Pleistocene park

Bisons at the Pleistocene park

By the time the Zimovs moved, the camps had shut down. Their remoteness was what they wanted: freedom from the vigilant eye of the Communist Party.

“To be a prophet, you must live in the desert.”—Mr Zimov.

A geophysicist and contrarian, Zimov founded the Northeast Science Station (NESS) for Arctic research. Today, several insights on thawing permafrost are drawn from his studies.

Understanding the Permafrost Thaw

permafrost—forzen soil

As global temperatures rise, the Arctic temperatures rise faster, in some areas registering 8°C warmer than only a decade ago. The real issue is once Arctic permafrost (a thick layer of frozen soil) begins to melt, its million year old deposits of minerals (carcasses, and plant material) are exposed, becoming food for microbes, which convert it into CO2 and methane—greenhouse gases. As we already know, these gases in turn accelerate the planet’s warming, and therefore also accelerate the thawing of the permafrost, creating a vicious feedback loop with possibly catastrophic consequences.

“It’s not anything we’re doing directly, and that makes it far harder to control.”—Robert Max Holmes, deputy director of the Woodwell Climate Research Centre

Northern Permafrost contains 1.600bn tonnes of carbon—twice as much carbon as is currently in the atmosphere. The issue with thawing, is that there is no consensus on how it will actually thaw: eg. all at once, or gradually, or creating lakes that attract more microbes…“The more permafrost is studied, the more scientists find surprises out there that they don’t know enough about”—the Economist.

Zimov’s Solution: Radical Rewilding at the Pleistocene Park

the Pleistocene epoch – about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago

the Pleistocene epoch – about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago

“Every scientist now appreciates the importance of the carbon in the permafrost, a lot of that can be traced to Zimov.”—Max Holmes, deputy director of the Woodwell Climate Research Centre

Zimov, albeit a polarising figure, remains a leading scientist in understanding permafrost thaw. Today, his research center NESS has become a global hub.

Following his extensive studies he has found a radical solution: returning the Arctic to the Pleistocene epoch’s ecosystem: a grassland known as the Mammoth Steppe—back when woolly mammoths, bisons, reindeers, lions, and wolves roamed the icy north. His project would be to rewild the Siberian tundra in order to bring back the grass. The reintroduction of large mammals would tamp down moss, knock down tress, and churn up the soil, allowing the grass to flourish again. Grass in turn reflects more light and reduces the amount of heat absorbed by the soil.

Putin orders Russian government to hit Paris agreement targets by 2030

Most importantly, the animals would also compress the winter snow, which creates a thick layer that does not allow the cold temperatures to reach the permafrost below. The thinner layer of snow would cool the permafrost more in the winter months, ensuring that it does not thaw in the summer.

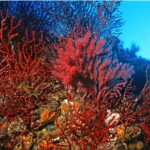

In order to achieve this, Zimov has created the Pleistocene Park, rewilding a mixture of Pleistocene surviving herbivores: Yakutian horses, bisons, musk oxen, elk, reeindeers, sheep, yak and kalmyk cattle. The reintroduction of these animals has in fact turned the mossy and wet tundra into a thriving grassland.

So far, Zimov’s results are promising. The animals have helped grasslands re-emerge. The average annual soil temperatures in grazed areas are 2.2°C cooler than in the nextdoor tundra, and more carbon is being sequestred by the grassland too.

Zimov hopes to scale his project to other areas in the Arctic. Their long-term dream is to host woolly mammoths again one day. They have formed a partnershing with Harvard scientist George Church who is researching how to revive these ancient beasts using CRISPR gene-editing technology and elephant genes.

Source: One Russian scientist hopes to slow the thawing of the Arctic, the Economist.