Bruno Manser is a unique soul: a Swiss medical student turned Alpine herdsman turned member of the Penan nomadic tribe turned Malaysian Enemy of the State turned international environmental activist turned environmental legend.

Bruno grew up in a normal family in the outskirts of Basel, Switzerland in 1954. From a young age he was fascinated by nature: he would insist on camping in his home’s backyard, even if it snowed. In seventh grade, during a school trip in the mountains, he took some morning glory seeds knowing they have similar properties to LSD, resulting in him getting too high to continue the trip. At age 19 his strong convictions on freedom, Taoism and Zen-Buddhism lead him to refuse the Swiss mandatory army service, which led to him being in prison for four months.

During his twenties, after dabbling in medical school, he decided that being close to nature was the only way to achieve true freedom, prompting him to leave for the mountains of Garubunden where he enrolled in Agricultural studies and lived for several years as a herdsman. During his time in the Alps he realised a different understanding of meaning, he mustfind and know people who live self-sufficiently and without money, people that couldn’t be found in Switzerland. So he organised a journey to Borneo, a trip that will radically transform his life and purpose.

By 1983 he was on his way to Bangkok. An avid speleologist (someone who studies caves) he travelled through Thailand by train stopping to explore its caves. By the time he reached the Malay border he thought to test his stamina and ability to live from nature by isolating himself from the village of a small island and focus six weeks eating from the land, with no local knowledge, which results in several poisonings. A month later, Manser travels to Kuching in Borneo aware of a British cave expedition about to begin to the off-bound area of Gulung Mulu National Park. He hopes to join them to obtain the necessary permits to enter the “protected” area. The English speleologists cave to his please, and with them he enters Penanland for the first time.

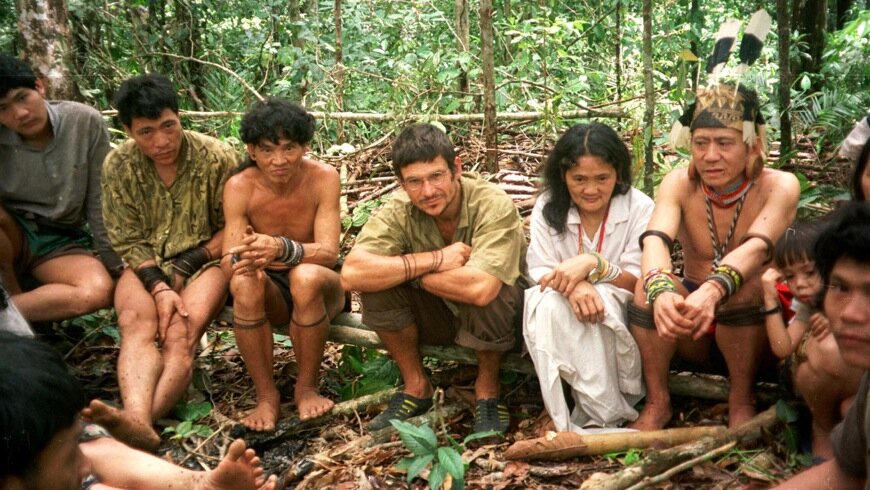

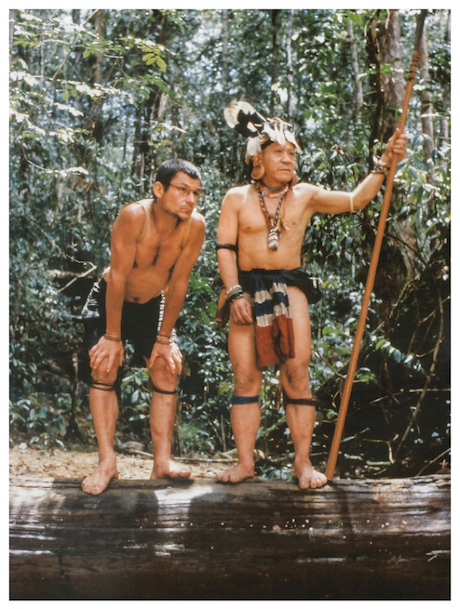

After the cave expedition Bruno finds the Penan tribe, who he lives with for six years, integrating with their nomadic hunter-gatherer existence in Borneo’s ancient rainforests. He learns their their language, their hunting methods, their healing formulas, their weaving techniques, as well as their incredible ability to share: “conflicts of ownership are completely unknown to the nomads, because their community is based on the principle of sharing.” Nothing the Penan use comes from the outside, everything is fashioned from what the forest provides. Bruno is eventually accepted by everyone as laki Penan, the Penan Man. Far away from Swiss “civilisation” Bruno found meaning through a life of simplicity, tranquillity, endurance, but also of compassion and selflessness.

In 1985 the blissful tranquillity of the clear cascades and swathes rainforest were disturbed by the unnatural noise of chain saws. For the Penan this noise was unheard of and unbeknownst to them they were listening to the beginning of the end of their paradise. For Bruno reality hits, the civilisation he escaped is coming back to haunt him, tearing down century old trees and destroying his new home. A dark awakening descended upon him: “My heart weeps as in a dirge — does the paradise really have to die, giving way to chainsaws and bulldozers? An eco-system, like an organism, which, untouched for millennia, has evolved in all its variety.”

One year into living with the Penan, Bruno used his knowledge of the outside world to write to the authorities. Later, another Swiss traveller joined the fight, Roger Graf. He met Bruno in Sarawak (Penanland in Malaysian Borneo) and commited to helping them once he returns to Europe. By 1986 Graf obtained over 6800 signatures on a petition to save the last indigenous people of Sarawak and founded the Pro Penan Association supported by Greenpeace.

In the jungle, Bruno met with leaders from other Penan tribes and villages to discuss a blockade to peacefully protest against the loggers. The protest and blockade began in March of 1987. 4700 people from 26 Penan and Kelabit villages blocked access roads to loggers for eight months, preventing over 1600 loggers from entering with 210 bulldozers. Manser and the Penan formally requested the Malaysian Government to establish a natural reserve and put an end to the massacre. Delegates of Penan people even travelled to Kuala Lumpur to plead with the government, however Malaysia’s Prime Minister Mahatir Mohamed’s stance was clear, bending to corporate greed, and realising the Penan’s best weapon was Bruno Manser, he placed a bounty on his head: anyone who brought Bruno to the authorities would receive around $25000 in compensation.

By 1988 Bruno was classified as an enemy of the state, while outside of Malaysia, a completely different story circulated. The image of Bruno as a spokesman for the Penan became a media sensation, with international human rights and environmental NGOs joining the fight. By the end of 1988 the fight was gaining momentum: Switzerland declared a boycott of tropical timber, whilst the European Parliament placed a limit on import of tropical timber. This was a big blow to the Malaysian government, who was the world’s largest producer of tropical timber (the ban was reversed in 1992). The same year film producers heard of Bruno’s story and three movies were produced about Bruno and the Penan fight: Tong Tana; Blowpipes and Bulldozers; and A Journey into the Heart of Sarawak.

In January 1990, Bruno’s Dad became sick, and a friend was sent to Sarawak to tell him the news. After six years in the jungle Bruno decided to return home and keep fighting for the forest from Switzerland. As an enemy of the state, he was forced to escape from Malaysia with a fake passport and a disguise. His exit was successful and he assumed his role of external spokesperson for the Penan. Upon his return to Europe, he had interviews and meetings every day, he also founded the Bruno Manser Foundation (BMF). By July 1990, protests and hunger strikes were organised outside Malaysian embassies in over 13 countries. Despite all of these efforts, back in Sarawak the situation deteriorated, every day 12sqkm of forest was torn down, destroying the Penan morale and threatening their existence. They described the situation as “feeling like fish who have been thrown onto land.”

A year later, the G7 summit was in London, and Bruno saw an opportunity: he entered the high-security zone, climbing up a lamppost and attaching himself to it with a heavy chain, then hanging a banner that read “G7? SARAWAK? FOREST? DESTRUCTION? HUMAN RIGHTS! VIOLATIONS! MORATORIUM NOW!”

Throughout the 90s Bruno travelled undercover back to Penanland. With his strong campaigning in Europe he had angered Malay officials, so every time he returned to the country, he needed to hike in through neighbouring Brunei or Kalimantan in Indonesia. In January 1992, Bruno iwass invited to Hollywood. Film writer David Franzoni was deeply intrigued by his story and Bruno signed a contract giving Warner Bros the right to film his life. For this he received $20000 a year, his only income until the film was dropped in 1998.

During the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, Bruno paraglided from the Corcovado peak into the Maracana Stadium with a group of American and Brazilian parachuters. They landed during the break of a football match with 100,000 spectators. Their message: “From Borneo to Brazil, Save the Rainforest, Respect the rights of indigenous people.”

Later that year, Bruno Manser travelled to Tokyo. At the time, the Japanese had converted 36 percent of globally traded tropical wood into disposable chopsticks, fast-food boxes, pallets and timber formwork each year, 86 percent of which came from just two Malaysian states: Sarawak and Sabah. Marubeni was the largest manufacturer in Japan, accused of illegal felling, was single-handedly driving deforestation in Borneo. Bruno led a hunger-strike, dressed only in a loin-cloth outside of the Marubeni headquarters that last many week. Japanese activists joined the strike and together they gained attention within the company. Marubeni promised higher standards, but without publishing their import records their compliance was unclear.

In 1993 the deterioration of Sarawak was deeply felt by the Penan. Their rivers were being depleted by dynamite fishing whilst their rainforest was destroyed by the timber industry. This caused a famine in the community. Yet their resistance persists, and hundreds of men, women and children built barricades against the continuous invasion of bulldozers. As a sign of solidarity with the Penan, Bruno organized a public fast in Bern, demanding that Switzerland reinstate its ban on tropical wood. After 60 days of fasting, Bruno is on the verge of death, only then does the Swiss government propose a new law: a mandatory declaration of wood and wood products. Such regulation would automatically exclude illegal Malaysian timber. The proposal is later abandoned.

In 1994, Bruno Manser expanded his and his foundation’s interest to other threatened rainforests and indigenous communities, through travels to meet the Ituri in Congo and to Greenland to meet the Inuits. He also received an award for Environmental Conservation by the Prince of Lichtenstein. During his acceptance speech he pleaded with listeners to believe in the power of choice, to choose wisely and not purchase tropical timber.

The late 90s were a wild mix of strong campaigning techniques and stealth visits to Borneo. The most outrageous stunt, performed by Bruno and Jacques Christinet was televised. Bruno and Jacques dropped 800 metres with an auxiliary cable on to the Klein Matterhorn aerial cable-car, hanging banners urging Switzerland to abandon its timber imports. During their descent they reached a speed of 140km per hour riding on a self-made rider with steel wheels and bearings. Other examples of his actions include paragliding uninvited into WEF in Davos and parachuting into a stadium in Malaysia offering a live goat to the President in sign of peace for Eid Mubarak.

In February 2000 he travelled back to Sarawak accompanied by a Swedish film crew to film Tong Tana II. In May, are the Swedish film crew had left, Bruno was alone in Penanland. He was last seen beginning an ascent of Batu Lawi, a mountain he knew well from his years in the Rainforest. Bruno never returned from Batu Lawi, his body was never found. His Penan friends searched high and low to no avail. By 2005 Bruno was officially declared dead.

Whether Bruno disappeared in his beloved forest, or was silenced once and for all by his enemies remains a mystery. All we can do is ponder on the life of this incredible man, on his fight against the devastation of the world’s forests, on his commitment to justice in an unfair fight, on his palpable courage against corporate and political greed.

I share Bruno’s life story in the hope it inspires you to live for justice, to preserve our rainforests, to make small changes in our day to day lives to continue Bruno’s fight. As of February 2020, 50 percent of the Borneo rainforest has been deforested.

Isabella Cavalletti is a storyteller and co-founded eco-nnect.