“Marine regulations in Mexico either have their origin in the fishing law or in environmental rules. Historically, the fishing industry has always influenced regulation to the point that fishing laws were pretty much written by the industrial tuna companies, that of course protected their interests above all. And in the case of the environmental laws, well, those laws were drafted in my house.”

I met Mario Gomez on a warm February morning in the restaurant of the La Catedral hotel in La Paz, Mexico. He was in between important visits — meeting a seventh generation shark fishing community in Agua Amarga and then speaking at the Our Ocean Conference in Panama — so I felt fortunate to cross paths with him and his team and join their weekly breakfast briefing.

Mario runs a myriad of organisations, all working together to achieve the same final goal: increase the amount of functioning Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in Mexico. It all started with his work in public policy in the 80s.

“In the 80s I was part of an ardent group of activists, we were all friends. Mostly we worked to protect Mexico’s forests and jungles. During that time we thought it was necessary for the Mexican government to establish a Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources, including fishing. This is why Beta Diversidad was formed, a policy lobbying NGO. Eventually through this governmental work, we were part of the long process that established the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas of Mexico (CONANP). This is the governmental body that now has the ability to operate and administrate Mexico’s protected areas. Within these there are seven different categories: Voluntary Conservation Area; Sanctuary; Natural Monument; Protected Area of Natural Resources; Protected Areas of Flora and Fauna; Biosphere Reserve; and National Park. Then within our activist group we each chose an area to focus our public policy work on, I chose the oceans.”

As we sit down for breakfast, Mario has an easy yet commanding demeanor. In classic Mexican hospitality he offers me anything from the menu. The team begins to order every style of egg available. We are 12 people, and every so often someone walks by and stops to catch up with Mario. Clearly he is a very admired and known figure within the community. I already knew that he had been instrumental in establishing the Revillagigedo National Park (Revi), North America’s largest no-take MPA. It has been a dream of mine to explore Revillagigedo’s underwater beauties for years. Revi is on every experienced diver’s bucket list and sits on top of mine. So I asked him, how did he achieve that?

“Six years ago we established the National Park of Revillagigedo. Within the seven categories of protected areas, National Parks are the most restrictive, no fishing or industrial activity is allowed. Revillagigedo today is one of the largest protected marine areas in the world, measuring 147,933 kilometres. We managed to secure this because we demonstrated to the Government that it wouldn’t affect local fishing communities. The archipelago of Revillagigedo is 400 kilometres south of Cabo San Lucas, artisanal fishers don’t go there, nor do sport fishermen, only the large industrial tuna and shrimp vessels can. We also conducted a study to prove to the industry that only 4.8 percent of their total catch came from that area. Of course now the industrial vessels fish along the margin of the MPA and their catch has overall increased.”

MPAs are a controversial topic within ocean conservation. This is because they are used as political instruments rather than for true conservation. For example in Europe bottom trawling, one of the most destructive forms of fishing in the world, is still allowed within so-called MPAs. This is what makes Revi stand out, absolutely no fishing is allowed.

The Revillagigedo archipelago is in the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Baja California Sur and it’s Mexico’s most remote territory. Composed of four volcanic islands and right on the Pacific corridor, it’s teeming with life: from great whites, schools of hammerheads, hundreds of dolphins, whale-sharks, oceanic manta rays and many species of migratory whales.

“Worldwide Revillagigedo is heralded as a conservation success. The MPA measures five percent of the Exclusive Economic Zone of Mexico. So when it was approved as a super rigid, highly and fully protected area it was a direct assault to the tuna and sardine industry that had been controlling the chamber of fishing for the previous four decades. They were not used to a total fish ban, rather the industry was used to deciding where the subsidies went, setting the quotas, creating their own sustainable labels etcetera… but with Revillagigedo a strong precedent was set.”

In Mexico, many fishing laws only benefit the industry’s interests. For example, a handful of companies retain full exclusivity of certain highly commercial species: sardines, shrimp and tuna. Despite their high revenues, the industry also takes home over 80 percent of the national fishing subsidies. Conversely, Mexican artisanal fishers’ livelihoods are being threatened by the stark decline of fish stocks due to the industry’s destructive methods. The whole system was written and designed to benefit a few big corporations and ultimately the Baja California Sur’s local fishers are the ones suffering the consequences.

I asked Mario if there is a way to help artisanal fishers access more subsidies?

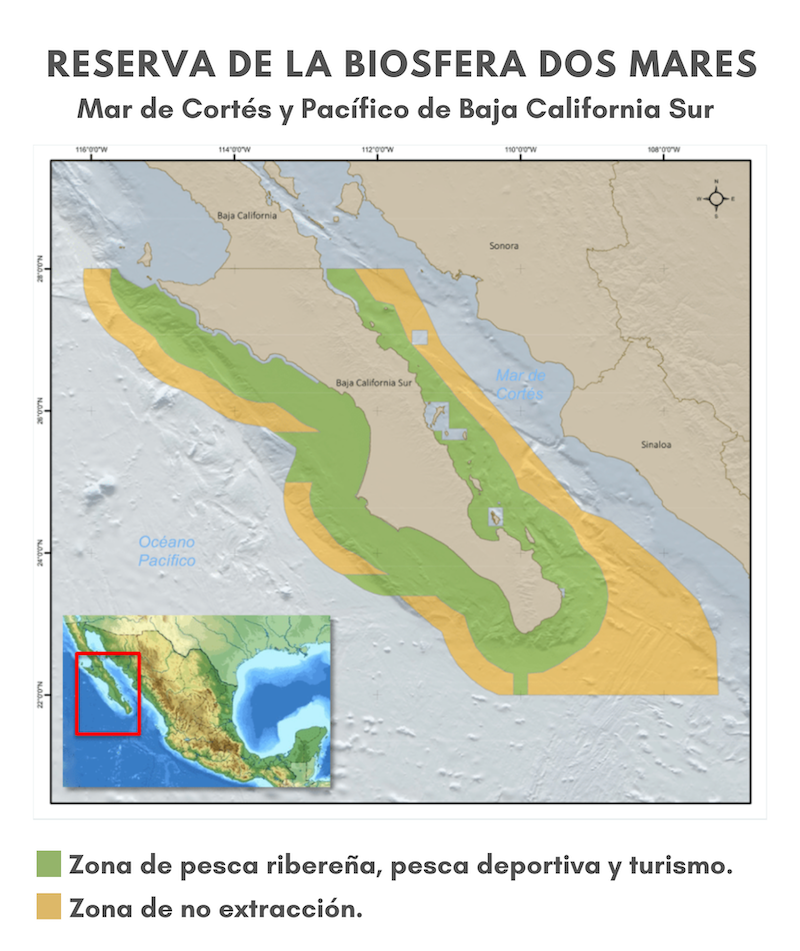

“Yes, we run an NGO called Depesca (Desarrollo Pesquero Sustentable). Depesca represents the interests of artisanal fishers. Technically they already have shares within the fisherman confederation, but the industrialists, the fish farmers, and the authorities are also in the confederation, so the voice of the coastal fishers is severely diminished. And since they have no resources, they are not well organised. Meanwhile, the industrialists have money for management, lobbying, and to convince legislators, authorities, etcetera… So the idea with ‘Depesca’ is to help the fishermen organise. However, in the last five years, we’ve been focusing on a new strategy, we are trying to implement another MPA, a Biosphere Reserve that would span the coast of Baja California Sur, we call it Dos Mares.”

A Biosphere Reserve is a category below National Park status. This means that artisanal fishers would be allowed to continue operating, whereas industrial vessels would not.

“To do this, first we have to convince the commissioner of natural protected areas to decree a Biophere Reserve, and last week he told us: “the only thing I need is for the coastal fishermen to raise their voices and publicly ask me to implement it.” So, we launched a communication campaign so that the Commissioner of Natural Protected Areas, the Minister of the Environment, the State Governor, and the President himself, feel that the fishers are asking this of them, but it is a difficult process.

“Essentially, the process is that of socialising the Biosphere Reserve, and socialising the reserve is very complicated. Wendy Higuera is a leader in her community and in her town, and half love the idea and the other half oppose it. So we are learning why certain people have issues with it, and it’s basically due to lack of knowledge and misinformation.”

At the weekly meeting, Wendy and Manuel Higuera are present. They are two local fishers from the town of Lopez Mateos in Magdalena Bay, about 300 kilometres north-west from where we are. Wendy is leading the campaign to push for the reserve and is the President of Depesca. They drove here to visit another fishing community near La Paz, Agua Amarga. Wendy explained how local fishers will benefit.

“We know that by conserving we are going to increase the mass of fish, we are going to improve our fishing and we are going to take advantage of resources that we have not been able to due to the industry’s interests. So I’m talking to other communities explaining to them that we can use our traditional fishing gear in a responsible manner, that we can use our boats for tourism purposes in certain seasons, and that our catch will be higher. I’m speaking to them in their language, from one fisher to another, so that they understand that ultimately the Biosphere Reserve would remove industrial fishing from our shores allowing our fish to reproduce. And that we don’t want to convert them all into tourist operators, we want to preserve their way of life, because our life is fishing.”

Magdalena Bay, where they live, is known worldwide as a breeding area for gray whales and for its yearly sardine runs. I had just visited the famous bay the day before and was awe-struck by the grays’ spy-hopping behaviour and friendly attitudes—spyhopping is when a whale bobs its head out of the water to check you out. To someone accustomed to the empty blues of the Mediterranean, MagBay seemed bountiful. I ask them what, if anything, has changed in their lifetimes? Manuel responded quickly.

“The shrimp industry began fishing in our hometown when I was quite young, when I first began fishing. Back then you could fish directly from the shore and there were many, many species. As shrimping increased, the species decreased. The shrimp boats drag at night and have small mesh nets that take everything with them — clams, turtles, guitar sharks, starfish, octopus, snails, small fish — everything is taken out and thrown dead overboard the next day, this continues on and on and on, night after night. A lot of the bycatch fish are juveniles and haven’t even made it to breeding size, this affects the reproduction of the species immensely. Our fish stocks have halved as a result, and many species have disappeared.” The shrimp industry has the world’s worst bycatch trackrecord, for every 1 pound of shrimp caught six pounds of bycatch are thrown out.

Wendy and Manuel have witnessed the emptying of the oceans. Their testimony reminds me of a very gut-wrenching quote by marine biologist Dr. Sylvia Earle. In a recent interview she was asked where the best diving in the world was? “Everywhere in 1970,” she replied. Essentially, before industrial fishing. Mario also spoke of their work.

“Wendy and Manuel are trying to spread the correct information and organise the various communities under one leadership. Hopefully this solves the confusion about what rules are implemented under a Biosphere Reserve and how they can benefit from it. Ultimately, the most important thing to consolidate a marine protected area is the process of acceptance and governance of the community that lives in it, this is what ensures that the protected area will be effective tomorrow. The management of the natural area is that the community understands it, manages it, knows it, and participates in its design.

“For example, a big problem is the issue of surveillance. It is impossible for governments to put a policeman in each tree to prevent illegal fishing, it is impossible for each fishing gear to have an inspector. What has to be done is to strengthen the community in such a way that they participate in the surveillance processes and the authority simply reacts to illegalities. But persecuting constantly is impossible. In other words, the sea is so extensive that it is economically unfeasible, these community vigilance committees must be formed once they are organised, once the leadership is built.”

I asked Mario what else do you need to do for the Biosphere Reserve Dos Mares to be implemented?

“There is a process to give birth to a reserve. You first have to carry out and submit a justifying study that is required by law. That is done by CONANP together with the source, which is Beta Diversidad in this case. And that study, because it contains all the legal, technical, ecological, biological, economic, social, tourist information, etcetera, is very complex. We have submitted it to the consideration of the new Commissioner for his team to review, and a large number of institutions can participate in it or oppose it, especially scientists.

“When you decree a reserve or a natural protected area, normally your natural enemy is the fishing industry and the fishing authority. However, in this case, we have a good number of NGOs that are either funded by the fishing industry or that work to preserve their interests. They are dedicated to “conservation”… but through the resources and interests of the fishing industry… There are scientists who work for the fishing industry and there are scientists who work for conservation. Those who work for conservation have less recognition because the industry has invested a lot more in its scientists and has placed them so that they can directly influence fishing policy instruments: laws, regulations. So now we need to make sure that the study is fully supported by the right interests and that dubious scientists are revealed.”

Porfiria Gomez finishes Mario’s train of thought as he is interrupted by a phone call. Porfiria works for Orgcas, another NGO kickstarted by Mario. Orgcas is operated by a group of 14 women that transition local shark fishing communities into tourist operators. Orgcas coordinated the meeting between Wendy and the Agua Amarga community.

You might also like: Fishing with Compassion

“We started the process five years ago, when Mexico’s new President Lopez Obrador arrived, he is the one who will take the final decision. However, the Minister of the Environment has already changed three times, as well as the Commissioner, so every time these important changes happen, we have to start the legal procedures all over again. At the same time, we are pursuing all the work with the communities and establishing the scientific review, therefore this year is very important, because next year we have elections again and we can’t risk another change in leadership. We need to ensure that the Biosphere Reserve is fully supported within the next eight months.”

If approved, the Biosphere Reserve Dos Mares would bring Mexico to its goal of protecting 30 percent of its oceans by 2030, while also supporting local fishing communities. For decades Mario and his team have been navigating a sea of vested economic and political interests within a country crippled by corruption and complex bureaucracy. Their dedication, courage and hard work brings me hope for future MPAs, returning the oceans to their former glory while creating a blueprint that can be applied worldwide.

Isabella Cavalletti is a storyteller and co-founded eco-nnect.