I recently visited my family in Costa Rica, and in each restaurant we visited, salmon was omnipresent. It was my grandmother’s go-to meal, she even ordered it when we went to the fishmongers. It made me wonder, with two bountiful coast lines, why is this country obsessed with a fish that isn’t caught in its waters? How has the salmon industry infiltrated our global consciousness with its “glamorous” appeal that has blinded locals from their own delicacies? What is it about salmon that has made its way onto virtually every menu on the planet? When did salmon become ubiquitous?

I was speaking to my father in Italy, and commented on the world’s salmon obsession. I asked him, when did salmon become a thing? He reminisced: well, I remember that when I was young in Rome salmon was considered a luxury, at the same level as caviar, just more accessible — we would buy it for celebrations. I thought of smoked salmon, blinis and caviar, and how salmon seemed to have had the opposite fate of lobster, going from occasional and high end to the second most consumed fish in the world. How did this happen? From Costa Rica to Jakarta, no matter which ocean you reside on, salmon is a thing.

Salmon farming began in Norway in the 90s as a solution to overfishing wild stocks. In fact, farmed salmon now accounts for 70% of salmon consumption worldwide and has played a key role in its meteoric rise — with a 500% production increase since 1995.

“The global salmon fish market size was valued at USD 14.87 billion in 2021 and is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.5% from 2022 to 2030. Increasing product launches in various forms including frozen, canned, and freeze-dried are likely to favor the overall growth.”- Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast

So I dug deeper into the salmon industry, big businesses with fishy marketing tactics tied to large seafood lobbies. In the US the American Heart Association includes salmon in its dietary recommendations to prevent heart strokes, twice a week it reads. This made me recall a similar tactic used by the dairy industry in its famous “Got Milk?” advertisements. Today evidence shows that milk doesn’t protect against bone fractures and is actually linked to certain types of cancer, yet those ads halted the decrease of milk consumption and actually increased it by 11%.

Salmon follows a similar story. In 2004, scientists found highlevels of polychlorinated biphenyls, a carcinogen known as PCBs, in farmed Atlantic salmon. Other more recent studies also show unsafe levels of antibiotics in farmed salmon. According to the WHO, people who eat even one farmed Atlantic salmon per month will accumulate unsafe levels of these toxins and can even show antibiotic resistance, which begs the question, when did corporate interests become synonymous with questionable national health recommendations?

The tie between corporate salmon interests and lack of federal regulation is staggering. An investigation conducted by the General Accounting Office revealed that the FDA inspected only 86 samples out of 379,000 tons of salmon in 2017. In fact, for the general public it is often very difficult to even know basic information, like whether the salmon is farmed, or which chemicals or antibiotics were used in the process. It seems the industry has remained conveniently ambiguous.

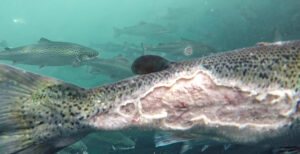

But let’s go back to the sustainability question: isn’t it better for the wild salmon population that we are mainly eating farmed salmon instead? Well in reality the farms are driving wild salmon to extinction. Picture this, millions of salmon spend two to three years in open-net farms of 10 or 12 cages that are anchored to the seabed, usually in coves in Norway, Chile, Alaska or Scotland. Similar to crammed chicken coups, this overcrowding leads to sea lice infestations and viruses. Farmers respond to these threats with pesticides — including neurotoxins — and antibiotics. These toxins are released into the local ecosystem, attacking wild salmon populations and the surrounding wildlife.

Salmon are carnivores, so farmers feed them unnatural fishmeal. Yes, farmed fish are fed smaller, wild-caught fish, such as anchovies, mackerel and herring, which are also known as forage fish. Apparently up to 30% of wild-caught fish is turned into fishmeal. Usually these fisheries are found in West Africa or Peru, where trawlers are destroying local fish stocks to meet the rising demand for salmon. This has huge consequences on the local populations that rely on forage fish as their protein source and for the entire marine ecosystem: research demonstrates that this overfishing is a leading cause for the rapid decline in seabird populations.

What would truly sustainable salmon look like? Well, did you know that once upon a time, wild salmon migrations criss-crossed continental Europe and the USA? Virtually every stream in Northern Europe was full of wild salmon. Yet due to our shifting baseline syndrome — where our accepted understanding of the natural environment gradually changes due to our lack of memory or knowledge of its past condition — we have started to accept our empty rivers once thriving with salmon migrations. This is the result of an underlying problem: how governments and corporations work together to create unnatural global demand for products and industries located in the northern hemisphere, at the expense of the local culture.

Through my salmon investigation I started noticing a similar pattern in other food choices in Costa Rica. Virtually every tropical fruit grows on trees above your head, yet the supermarket aisles are filled with apples and grapes from Europe. Of course this is a country with 83% European descent. So it’s not salmon that is omnipresent, it’s Europe importing and imposing its culture. Did you know that we eat the same 20 vegetables in almost every corner of the globe? Despite the existence of over 20,000 plant species, zucchini and broccoli rule the world. The old world not only conquered cultures, it homogenized them too.

As my grandmother and I walked the supermarket aisles, deciding on what to eat for dinner, I suddenly realized that Europe’s dark history of conquest and arrogance was hiding the beauty and abundance that Costa Rica’s rich lands offer, which wasn’t only happening here but in many other colonized countries where native communities had diminished considerably. USA, Brazil, Colombia, Australia, to name just a few. Perhaps originally colonists had imported the foods and traditions they knew out of comfort, but today it seems that a new form of corporate colonization has taken hold, where products tied to Europe are marketed as better, healthier and more luxurious than local offerings.

Our food system is rotten and broken. Instead of celebrating diversity, heritage and natural abundance, we are still living within a framework influenced by our colonial past. To rewild our souls we must rewild our culture, and to rewild our culture we must rewild our food systems. To rewild our food systems we must rewild our plates.

So I offer some food for thought: next time you order salmon, think about how close or far you are from the now empty streams of Northern Europe. Isn’t it time to focus on bringing life back to the rivers rather than expanding a clearly harmful industry?

Isabella Cavalletti is a storyteller and co-founded eco-nnect.