scroll down for the Italian translation

Chiara Vigo, is the last known master of the byssus sea silk. She lives in the southernmost tip of Sardinia, on the island of Sant’Antioco. She was trained as a master by her grandmother. In fact the Vigo women can trace back their lineage of byssus weaving to 500 years ago.

“A master comes, a master goes. It has been done in my family for 28 generations now.”

For millennia the secret of how the byssus sea silk is woven from the slime produced by a Mediterranean clam, the Pinna nobilis, has been passed down from grandmother to granddaughter with very strict instructions that the sea silk must never be sold and the knowledge must remain within the female bloodline. Legend says that whoever breaks this pledge will be cursed.

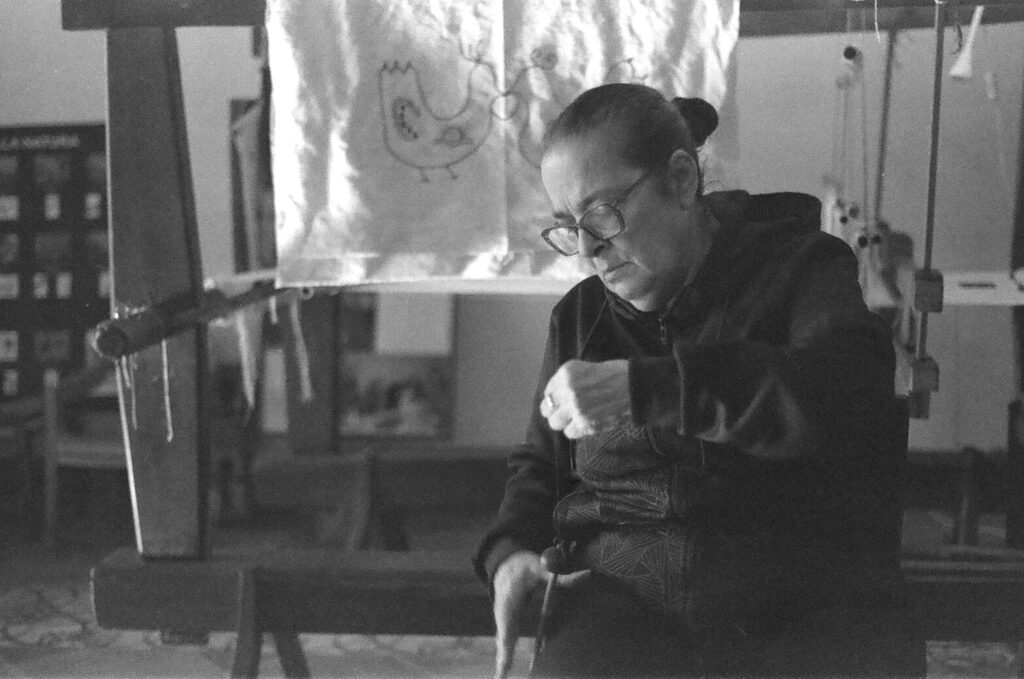

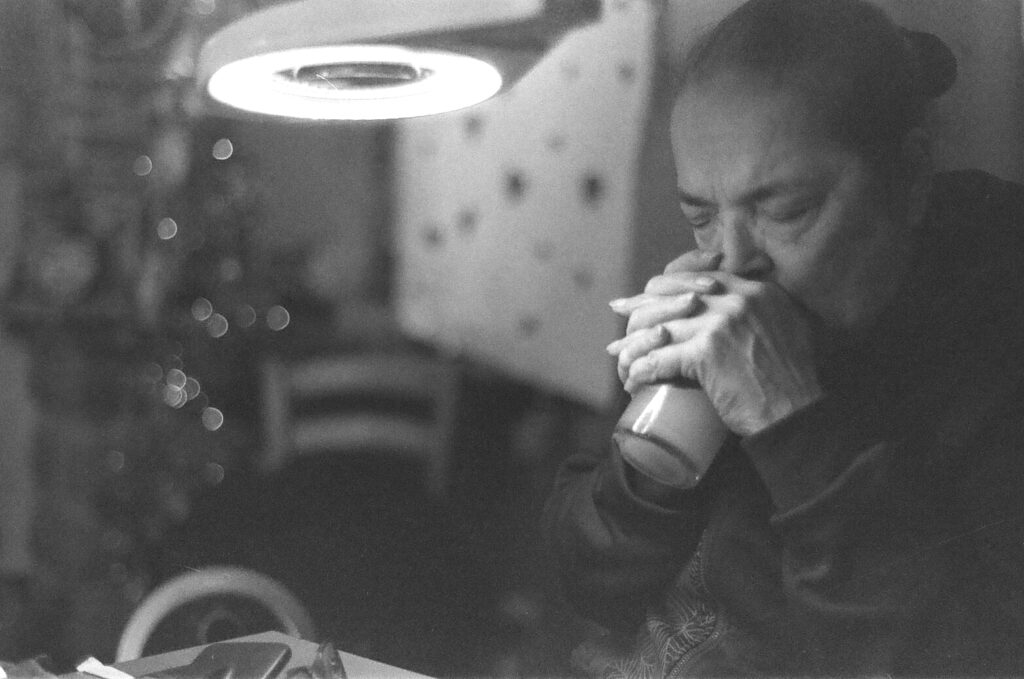

Earlier this year, I traveled with a few friends across Sardinia and we met with Chiara Vigo in her workshop in Sant Antioco. When we entered, we were three Italian women, following a thread: an urge to connect with the native mysticism that was buried by millennia of ecclesiastical persecution. Chiara greeted us warmly, like a grandmother welcoming her family. Her demeanour was gentle yet she spoke directly.

“Your generation is fascinating. You travel the world, to other cultures, to the Far East, to learn how to meditate, yet you don’t have to actually travel far, the knowledge is also right here in your home country. Do you know how to weave?”

She asked us simply. No, we replied in unison. Her workshop is home to her 200-year-old loom, an imposing and beautiful wooden structure that seems incredibly complicated to maneuver.

“In every culture across the world, women’s connection is through the art of weaving.”

Chiara only unveils the teachings of the art of byssus sea silk to her nine year old granddaughter, however she teaches weaving to everyone. Her door is always open as long as you’re not in a hurry, a sign on the door reads.

“A few years ago, it was about creating the thread that connected women. Which is neither given by the flashy dress, nor by showing off your brain. We don’t need to prove anything. As long as we are what we want to be. But what’s missing in my opinion right now is the essence, people just do things, but they don’t do it consciously.”

I asked, what makes byssus sea silk special?

“Byssus can never be traded, it can only be gifted. In the Old Testament when King Solomon says ‘the king went out at the door and at the sound his clothes were covered with gold’, He is talking about the byssus. There is no other fibre that changes with sound, how the vibrations hit the material the silk captures the light and makes it its own. This is why the byssus is placed in a sacred situation and how it becomes golden.”

Little is known about the Nuragic civilisation (1600-750BC) from Sardinia, yet the island is full of archeological sites from that era: from the tombs of the giants, to fairy portals and water temples. The Nuragic people were an oral culture, and no written accounts of their tradition have been found, only paintings and small bronze sculptures.

Legend says this civilisation was a very evolved matriarchy, similar to the Etruscans across the Thyrrenean Sea, and with connections all the way to the Phoenicians and the ancient Egyptians. In fact, stones from Northern Africa have been found in the temples. The High Priestesses that led these people were known to wear gowns with golden threads of byssus sea silk. The silk is referenced in several sacred scripts including an inscription on the Ptolemaic Rosetta Stone that dates back to 196 BC.

Every Spring, protected by nightfall on a full moon night, Chiara dives in a secret cove on the island to retrieve the pinna nobilis’ slime. It will take her about 100 dives to retrieve only 200g of slime, which becomes about 30g of yarn and 21 meters of thread.

The pinna nobilis is a species endemic to the Mediterranean. In 2016 a parassite known as Haplosporidian endoparasite spread to the Mediterranean via surface currents, which killed over 99% of the mollusc’s Spanish population. Since then, the disease has been slowly spreading across the Mediterranean. Today, it is a critically endangered species in desperate need of protection.

“The pinna lives for 25 years, reaches heights of one metre and ten, is the largest Mediterranean bivalve, and is stuck in the seabed for two thirds of its height. He has a jokester enemy: the octopus. If the octopus finds it open, it sticks out its tentacles, eats it and makes its home there, therefore she defends herself equipped with a sieve gland that is connected to her orifice. When she feels threatened, she swells the gland and closes the entrance with the slime.”

It’s thanks to the symbiotic relationship between the octopus and the pinna nobilis that we get the byssus, as without the octopus the pinna wouldn’t secrete the slime.

Chiara showed us a ball of byssus yarn, then told us to close our eyes and hold out our hand. She then asked us if we felt anything. No, we replied. When we opened our eyes she had placed a fist-size ball of byssus yarn on our hands. It is weightless, as thin as a string of hair.

“Once cleaned, it no longer has the weight and you can no longer feel it. Just cleaning this small ball of byssus can take 90 years, because when it comes out of the fin it is liquid, then as it touches the substrate it solidifies and becomes silk. To turn it into thread, you need to first clean it delicately with a brush. Imagine how much work goes into making a ball like that. So imagine how much work goes into making a shawl. What are we talking about? It takes years, unless you destroy half the Mediterranean, which is why I took the Water Oath.”

Chiara took the Water Oath in 1983. Her grandmother used to fish for the pinna nobilis by retrieving the slime and then eating the flesh, back when the Mediterranean was abundant with life. However, Chiara has had to adapt to the reality of the emptying seas, and with her oath she promised to retrieve the slime without killing the animal.

“Instead I chose to maintain through the Water Oath what it already was without modifying its essence. Naturally I have all the byssus of my grandmothers and my great-grandmothers to clean still. This ball is 300 years old.”

This makes me realise what a true Master Chiara is, she dives each year to retrieve byssus that she most likely will never weave. She is retrieving it for her granddaughter, just like her grandmother did before her, leaving behind a method that does not interfere with the ecosystem.

“Now I will use sound, I will change the fiber and make it capable of capturing the light, making it its own and becoming gold in light.”

Chiara walked over to her loom and began chanting a deep chant, in a mysterious unintelligible language. It reminded me of Buddhist monks, and I realised what she meant when she told us that we didn’t have to travel to the East to find truth.

“To me, making byssus is not using a spindle and it is not weaving. It is preserving for those who come what already was, without modifying it in the manufacturing and delivery ritual.”

Throughout Italy, a country synonymous with textiles and fashion, Chiara’s mastery has become a legend. Directors of large fashion houses have descended upon Sardinia ready to pay fat cheques for the mysterious golden thread. Yet if anyone else tries, the slime will not turn to thread, and the thread will not become golden. Chiara is a true testament to ancestral Italian wisdom, despite the contemporary capitalist and patriarchal Italian culture that surrounds her, the silk is not for sale, her mastery is only for her granddaughter’s ears. Yet her door is always open for those willing to listen to her wisdom, her integrity is as rare as the sea silk. She is a true master in a world where almost everything is for sale.

“If each of us followed what he has in his soul, there would be no climate crisis. If you love without ifs or buts, time passes peacefully. Masters of the arts should simply love and do nothing, love everyone as they are. Just take the beauty of each individual. We try to make the ugly become beautiful.”

You would also like: Regenerating the Heart of the Earth

Chiara Vigo è l’ultima maestra vivente di bisso, la seta del mare. Vive nell’estremità più meridionale della Sardegna, sull’isola di Sant’Antioco. È stata iniziata come maestra di bisso da sua nonna. Infatti, il suo lignaggio risale al 1500.

“Un maestro viene, un maestro va. Nella mia famiglia si fa ormai da 28 generazioni.”

Per millenni il segreto di come si tessesse la seta marina di bisso, prodotta dal muco di un mollusco mediterraneao, la Pinna nobilis, è stato tramandato da nonna a nipote attraverso istruzioni molto rigorose: la seta marina non deve mai essere venduta e la conoscenza deve rimanere all’interno della linea di sangue femminile. La leggenda narra che chiunque infranga questo giuramento sarà maledetto.

All’inizio dell’anno ho viaggiato con delle amiche attraverso la Sardegna e abbiamo incontrato Chiara Vigo nel suo laboratorio di Sant’Antioco.

Tre donne italiane all’insegna di una trama: l’urgenza di connetterci con il misticismo nativo sepolto da millenni di persecuzione ecclesiastica. Al nostro arrivo Chiara ci ha accolto calorosamente, come una nonna che accoglie la sua famiglia. Il suo atteggiamento era gentile ed il suo esprimersi schietto.

“La vostra generazione è affascinante. Viaggiate per il mondo incontrando altre culture, in Estremo Oriente, per imparare a meditare, ma in realtà non dovete viaggiare lontano, la conoscenza è anche qui, nel vostro paese. Sapete tessere?”

Ci ha semplicemnte chiesto. No, abbiamo risuonato all’unisono.

Il suo laboratorio è la sede del suo telaio centenario, una struttura bella ed imponente che sembra incredibilmente complicata da manovrare.

“In ogni cultura del mondo, il legame delle donne è sempre stato attraverso l’arte della tessitura.”

Chiara rivela gli insegnamenti dell’arte del bisso solo alla sua nipotina di nove anni, ma insegna a tessere a chiunque. La sua porta è sempre aperta, purché non siate di fretta, recita un cartello sulla porta.

“Un po’ di anni fa, la mia intenzione era di tessere il filo che collegasse le donne. Questo non è dato dal vestito appariscente, né dal cervello che non funziona. Non abbiamo bisogno di dimostrare nulla. Basta essere ciò che vogliamo essere. Ciò che manca, secondo me, è l’essenza. Le persone fanno le cose, ma non lo fanno consapevolmente.”

Ho chiesto, cosa rende così speciale il bisso marino?

“Il bisso non può mai essere commercializzato, può solo essere donato. Nel Vecchio Testamento quando il Re Salomone dice ‘Usciva il re sulla porta ed al suono le sue vesti si coprirono d’oro’, sta parlando del bisso. Non c’è altra fibra che cambi con il suono, come le vibrazioni colpiscono il materiale, la seta cattura la luce e la rende sua. Ecco perché il bisso è collocato in una situazione sacra e diventa dorato.”

Poco si sa della civiltà nuragica (1600-750 a.C.) della Sardegna, eppure l’isola è piena di siti archeologici di quell’epoca: dalle tombe dei giganti, ai portali delle fate e ai templi dell’acqua. La leggenda narra che questa civiltà fosse un matriarcato molto evoluto, simile agli Etruschi nel Mar Tirreno, e con connessioni fino ai Fenici e agli antichi Egizi. Le Somme Sacerdotesse alla guida di questa società erano conosciute per indossare abiti con fili d’oro di bisso. La seta è menzionata in diversi testi sacri, incluso un’iscrizione sulla pietra di Rosetta tolemaica che risale al 196 a.C.

Ogni primavera, al calare della notte protetta dalla luna piena, Chiara si immerge in una baia segreta dell’isola per recuperare il muco della pinna nobilis. Le serviranno circa 100 immersioni per recuperare solo 200g di muco, che diventeranno circa 30g di gomitolo e 21 metri di filo.

La pinna nobilis è una specie endemica del Mediterraneo. Nel 2016 in Spagna, il parassito Haplosporidian endoparasite ha ucciso oltre il 99% della popolazione spagnola del mollusco. Da allora, la malattia si è diffusa lentamente attraverso il Mediterraneo. Oggi è una specie gravemente minacciata che ha bisogno urgentemente di protezione.

“La pinna vive per 25 anni, raggiunge altezze di un metro e dieci, è il più grande bivalve mediterraneo e si infissa nel fondale per due terzi della sua altezza. Ha un nemico monello: il polpo. Se il polpo la trova aperta di notte infila i tentacoli, la mangia e ci fa la casa. Per questo si difende con una ghiandola a setaccio collegata al suo piede, una valvola che attraversa il mantello e si appoggia nell’orifizio esterno. Quando si sente minacciata, rigonfia la ghiandola e chiude l’ingresso con la bava. Quando il polpo si rintana, spruzza il muco all’esterno che come tocca l’acqua si solidifica e diventa seta purissima, imprigioando tutto ciò che incontra”

È grazie alla relazione simbiotica tra il polpo e la pinna nobilis che otteniamo il bisso, perché senza il polpo la pinna non secernerà la bava.

Chiara ci ha mostrato un gomitolo di bisso, ci ha chiesto di chiudere gli occhi e tenere la mano tesa. Ci ha chiesto poi se sentissimo qualcosa. No, abbiamo risposto. Quando abbiamo aperto gli occhi, aveva messo un gomitolo di bisso nelle nostre mani. È talmente leggero da essere impercettibile, sottile come un filo di capelli.

“Una volta pulito, non ha più peso e non lo si sente più. Solamente pulire questo piccolo gomitolo può richiedere 90 anni, perché quando esce dalla pinna è liquido, poi quando tocca il substrato si solidifica e diventa seta. Per trasformarlo in filo, devi prima pulirlo delicatamente con una spazzola. Immagina quanta fatica ci vuole per fare un gomitolo del genere. Quindi immagina quanto lavoro ci vuole per fare uno scialle. Di cosa stiamo parlando? Ci vogliono anni, a meno che non distruggi metà del Mediterraneo, ed è per questo che ho fatto il Giuramento dell’Acqua.”

Chiara ha fatto il Giuramento dell’Acqua nell’anno 1983. Sua nonna pescava la pinna nobilis recuperandone la bava e poi mangiandone la carne, quando il Mediterraneo era ricco di vita. Tuttavia, Chiara ha dovuto adattarsi alla realtà dei mari che si svuotano, e con il suo giuramento ha promesso di recuperare il muco senza uccidere l’animale.

“Invece ho scelto di mantenere attraverso il Giuramento dell’Acqua ciò che già era, senza modificarne l’essenza. Naturalmente ho ancora tutto il bisso delle mie nonne e delle mie bisnonne da pulire. Questo gomitolo ha più di 300 anni.”

Questo mi fa capire che tipo di Maestra sia Chiara, pura ed integra, si immerge ogni anno per recuperare il bisso che probabilmente non tessera mai. Lo sta recuperando per la sua nipotina, proprio come sua nonna fece prima di lei, lasciando dietro di sé un metodo che non interferisce con l’ecosistema.

“Adesso userò il suono, cambierò la fibra e la renderò capace di catturare la luce, farla sua e diventare oro nella luce.”

Chiara si è avvicinata al suo telaio e ha iniziato a cantare un canto profondo, in una misteriosa lingua incomprensibile. Mi ha ricordato i monaci buddisti, ed ho capito cosa intendesse quando ci ha detto che non dovevamo viaggiare verso est per trovare la verità.

“Per me, fare il bisso non è usare un fuso e non è tessere. È preservare per coloro che verranno ciò che già era, senza modificarlo nel rituale di produzione e consegna.”

In tutta Italia, un paese sinonimo di tessuti e moda, la maestria di Chiara è diventata leggendaria. Direttori di grandi case di moda si sono recati in Sardegna pronti a pagare grosse cifre per il misterioso filo dorato. Ma chiunque altro provi non riuscirà a trasformare la bava in filo ed il filo non diventerà dorato. Chiara è un vero esempio della saggezza ancestrale italiana. Nonostante sia circondata da una cultura capitalista e patriarcale la seta non è in vendita; la sua maestria è solo per le orecchie della sua nipotina. Eppure la sua porta è sempre aperta per coloro disposti ad ascoltare la sua saggezza, la sua integrità è rara quanto la seta marina stessa. È una vera maestra in un mondo in cui quasi tutto è in vendita.

“Se ognuno di noi seguisse ciò che ha nell’anima, non ci sarebbe la crisi climatica. Il problema non si risolve perchè non ci si vuole mettere insieme e collaborare. Se ami senza se e senza ma, il tempo scorre serenamente. Il Maestro dovrebbe semplicemente amare e non fare nulla. Amare tutti così come sono. Basta cogliere la bellezza di ogni individuo. Cerchiamo di rendere bello ciò che è brutto.”

Scritto da/ Written by: Isabella Cavalletti, tradotto da / translated by Carola Rovati