Angus Morrison is working to export organic fruit pulp from the Peruvian rainforest. A goal that could bring immense benefits to the developed world, the Amazonian people, and the jungle itself

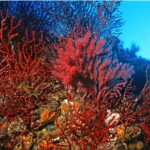

Deep in the Amazon rainforest, fruits with amazing nutrition profiles flourish. Some species, like açai, have already gained renown in the West for their promise to help people stave off illness, while others, like camu camu, are still relatively unknown. Now Angus Morrison, an eccentric British inventor, wants to use fruit from the jungle to push humanity toward a healthier and more sustainable path.

Morrison is working to become the first licensed exporter of organic fruit pulp from the Peruvian forest, a goal he says can bring immense benefits to the developed world, the Amazonian people, and the jungle itself. His company, Frutama, is located in Iquitos, a busy metropolis set on the banks of the Amazon River. It already sells fruit pulp around town and to popular restaurants in Lima, such as Amaz and Maido.

The next step is to make the product available internationally. “The idea of Frutama is to commercialise, sell, process, and take to Westerners what the jungle delivers naturally, give income to native people, and at the same time bring sustainable development”-Morrison explains.

Morrison has lived in Iquitos for five years, slowly building his business. Previously, he founded a pair of computer design companies in Great Britain before he grew disgusted with the abuses of Western consumerism and capitalism that he set out in search of a more holistic, sustainable lifestyle. He found it in the Amazon, facilitated by the powerful psychedelic drink ayahuasca. “It connected me with the intentions and connections of plants,” he says, a gift he hopes to share with others through Frutama. “We’re a bridge between the plants who want to help human beings,” Morrison says, “and human beings who want to help plants.”

He knows that some might find his ideas unconventional. “In the West, I would be regarded as a complete whack-job. A nutter,” he says. “[But] if Western consumers are consuming these fruits and they get better, healthier, stronger, they will get into these plants. Maybe they will want to help the Amazon.”

The venture comes at a critical time for the forest, which is actively being destroyed in pursuit of profit. Although the jungle has supported human life for thousands of years, its inhabitants need money to participate in the modern world, and for many, cutting down trees is the easiest way to make a quick dollar. The Amazon is the most bio-diverse region in the world, with over 40,000 species of plants identified in the jungle, and countless more still undiscovered—or already extinct due to deforestation, along with whatever potential they had to improve human health. The massive rainforest once covered roughly 2.1 million square miles, but some 20 percent has already been razed, mostly for lumber, slash-and-burn agriculture, and cattle ranching.

Through fruit, Morrison sees a way to save the forest before it’s too late. “If you develop and the natural world is still around you, you can make all the choices you want. If you destroy it, you have no choices left to make,” he says. “I want to make the Amazon worth more alive than dead.”

He and his business partner, an Irishman named Freddie Alexander, take trips up and down the jungle rivers to source their fruit and build relationships with the indigenous populations who still rely on the forest for their livelihood. By giving them the opportunity to make an income, they hope to slow the destruction of the jungle. “If communities are making a good living planting, harvesting, nurturing native species,” Morrison says, “that virtuous cycle will stop requiring people to chop trees for wood.”

Meanwhile, he sees the rest of the world turning inward and cannibalizing itself through greed, corruption, and poor diet. “The western world is devitaminized, demineralized. Cancer rates are through the roof,” he says. “The destruction is becoming obvious.”

The plants, he says, can help via their amazing nutritive potential. “Every fruit is extreme in its properties,” says Morrison. The açai berry is already well-known as a superfood, considered in some quarters to be the most powerful antioxidant in the world. It’s also a source of protein, fiber, calcium, iron, vitamin A, other important vitamins, minerals, and acids, and has gained a reputation for helping with sexual performance as well as heart and kidney function.

Camu camu, a sour-tasting red berry, is less known, but the fruit also has a wealth of vitamins and minerals, most notably one of the highest vitamin C contents in the world. A third fruit, aguaje, yellow with a brown scaly peel, also contains an enormous amount of vitamin C as well as beta-carotene, but has been gaining fame for a more whimsical reason: It’s rumored to help women grow larger backsides. Unfortunately, the preferred way to harvest the aguaje fruit is to chop down the tree, a practice Morrison hopes to mitigate by training people to scale the trunks instead and reap a sustainable harvest year after year. To fend off further deforestation or monocultures, he encourages his vendors to nurture a sustainable mix of native woods and fruit in their communities.

In Iquitos, Angus and Freddie are working on renovating what could one day be a beautiful house, a mansion on the popular tourist malecon that overlooks the Itaya river, the front wall lined with gaudy mosaic tiles imported from Europe in the early 1900s during the rubber boom. They plan to open a smoothie bar in the front of the house to quench the thirst of tourists and introduce them to the various fruits.

One day, they dream of building a mobile processing plant on a barge that travels up and down the rivers so they can purchase, process, and freeze the fruit right on the boat. For now, the company has a processing facility in the city, where machines, some of which Morrison invented himself, turn the fruit into pulp and freeze it. In an illustration of the challenges of doing business from Iquitos, which has no road access to the outside world, he recently took a trip to Lima to escort a new machine on a multi-day journey, first across the Andes by road and then on a boat down a tributary of the Amazon until it arrived at the jungle city.

Freddie Alexander and Angus Morrison are trying to bring organic Amazon fruit to the world

Despite the difficulties, Morrison is seizing the opportunity to help preserve his adopted home. “We have a real ability to affect change,” he says. “It could be incredible.”

by Frederick Alexander

https://munchies.vice.com/en_us/article/d753aj/can-fruit-from-the-amazon-save-the-world