Depending on how you define it, activism has a long history in so called Australia.

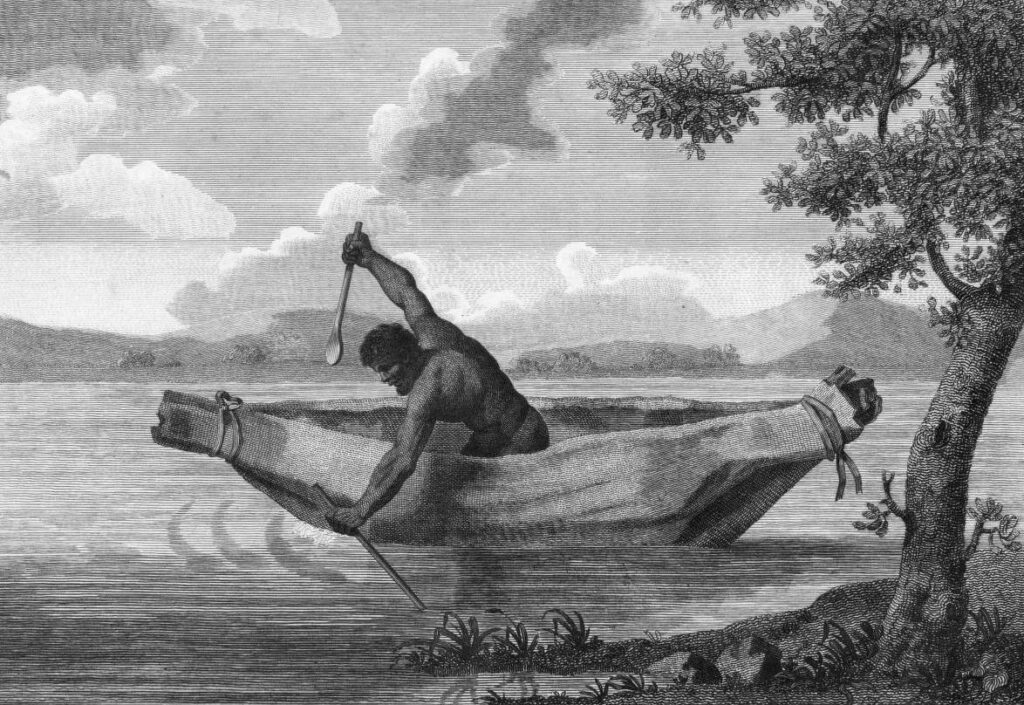

When Arthur Phillip — a former whaler and longtime servant of the British Navy — attempted to establish a colony on Gadigal land, he was resisted by Bennelong, Pemulwuy and the many Eora people who fought beside them. The Colony was established in the settlement of Sydney Cove, and early settlers invaded the nearby land of the Dharawal, Dharug, Awabakal, Darkinjung, Gandangara and Wiradjuri peoples. The fifth Governor of New South Wales, Lachlan Macquarie, effectively declared war on the “hostile natives”. Communities were massacred and native forests were felled, as settlements spread with the support of British agriculture and grazing methods that were imposed on the land. The Original Peoples of the Sovereign Nations that criss-cross the Australian continent and its surrounding islands, resisted an onslaught of violence and terror for over 100 years through a series of conflicts commonly referred to as the Frontier Wars. Musquito, Yagan, Windradyne, Tarenorerer, Tunnerminnerwait, Maulboyheenner, Truganini, Jandamarra and Dhakiyarr are some of the many figures of resistance who fought alongside their respective communities.

Eventually the colonies of New South Wales, Van Diemen’s Land, Port Phillip, Swan River, South Australia and Queensland united to form the Commonwealth of Australia. Resistance continued as communities lived in the face of the restrictions imposed on their culture and connection to Country by the newly formed state and federal governments. Foreign settlers also resisted British rule and imposition, reflected in the Rum Rebellion of 1808 and the Eureka Stockade of 1854, as well as the development of labour unions throughout the colonies in the 19th century.

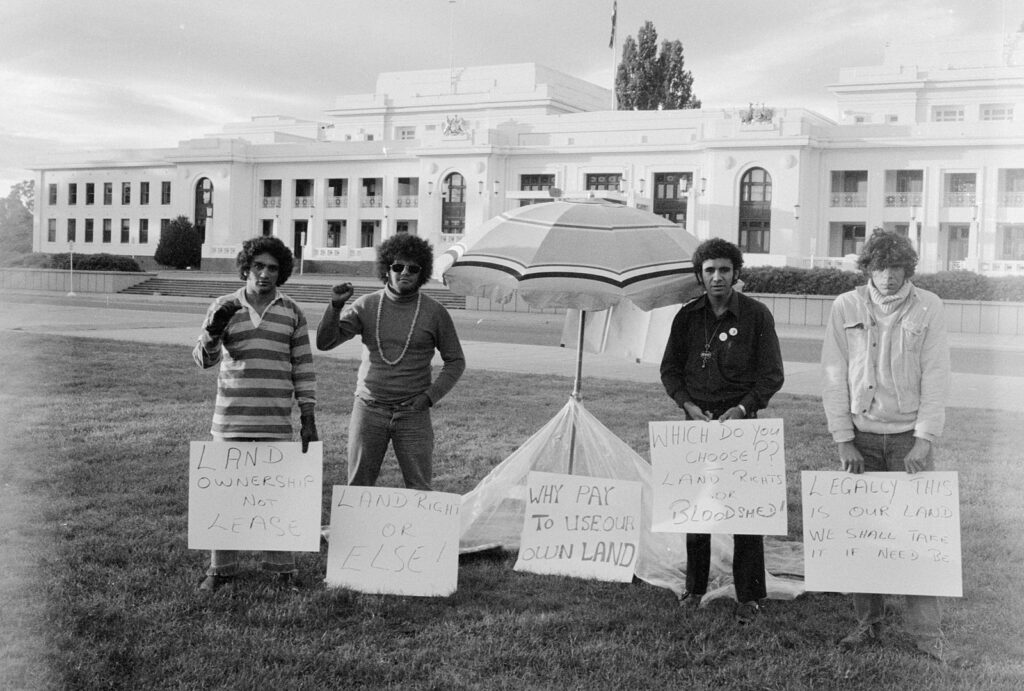

Unionism also influenced the development of the first politically organised Aboriginal activist group, the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA), formed in 1924, campaigning for rights to land ownership, citizenship, control of their own affairs and an end to the removal of Aboriginal children from their families. The AAPA was renamed the Aborigines’ Progressive Association and along with the Australian Aborigines League, they organised the first Day of Mourning on January 26 1938. It was the culmination of years of work, encouraging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activism across Australia, which led to the Yirrkala Bark Petitions, the Freedom Ride, the Wave Hill walk-off, the campaign for the constitutional referendum of 1967, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy and the Mabo Case.

The worldview and cultural practices of the Original Sovereign Nations of Australia, particularly their connection to Country, is well documented, and the outcry for civil rights was intrinsically linked to the protection of their territories. As the Australian population increased through waves of migration, the native landscape was destroyed to make way for industries that supported the growing number of settlements, particularly agriculture and grazing, the extraction of natural resources, and the eventual privatisation of land. Despite the ongoing desecration of the environment across the continent, it took time for settlers to develop a connection to the landscape and thus develop an awareness of the need for its protection, as well as the rights of the indigenous peoples who have always called it home.

Although many settlers campaigned for the rights of the Original Sovereign Nations of Australia and advocated for the protection of native plants and wildlife, the history books suggest the Australian conservation movement began with the creation of National Parks in the late 19th century. It was with the near extinction of the thylacine — also known as the Tasmanian Tiger — that environmental awareness spread through the dominant colonial culture, leading to koalas being declared protected species in 1937 and Tasmanian Devils in 1941.

The thylacine population of Lutruwita (Tasmania) was around 5,000 when the British settled there, but they were known to attack sheep and thus hunted by farmers. As the thylacine population dwindled, sightings became significant news, as standards at the time stated an animal could not be declared extinct until 50 years had passed without a confirmed sighting. In 1968, zoologist Jeremy Griffith and local dairy farmer James Malley conducted what has been described as the the most extensive recorded search for the thylacine in the history of Lutruwita. In 1972, they formed the Thylacine Expeditionary Research Team with Bob Brown, which concluded without discovering evidence of the thylacine’s existence.

“I’d read about the Tasmanian Tiger and its alleged extinction, and then I saw a black and white television program, I think it was Four Corners, on Lake Pedder.”

Nestled amongst the peaks of the Frankland Range in Lutruwita’s southwest, Lake Pedder was a once glacial lake adorned by a pink quartzite beach. It was often referred to as “the mirror of heaven”.

“I wanted to know more about what was going on, so I kept my eye out for a job in Tasmania. I was working on ships in the Pacific as a doctor, and I was reading a medical magazine, and there was an ad for a three month position in Launceston replacing a doctor who was travelling to England. So I came, applied, got the job and within a year, I ran into two guys who were looking for the Tasmanian Tiger.”

The search for the thylacine inspired Bob’s early explorations of Lutruwita’s famed wilderness. He travelled into the Tarkine and the island’s northeast, to places where the thylacine had allegedly been sighted.

“The sightings always led to some other animal which may or may not have looked like a Tasmanian Tiger. But this presumption that if you couldn’t identify something that you saw in the night, it must be a Tiger, needed to be met with a fair degree of clarity of mind, but the Tiger is extinct.”

Bob also became involved in the campaign to protect Lake Pedder. The Lake and its surrounding wilderness was protected by National Park status in 1955 but it was then revoked in 1967, as the Tasmanian government wanted to flood the Gordon, Serpentine and Huon Rivers as part of a hydro-electric generation scheme, which was pushed forward through the avid support of Premier Eric Reece (who was nicknamed “Electric Eric”). The eventual dam obfuscated Lake Pedder’s unique natural beauty, creating a sprawling reservoir that provides extra “storage” to Lake Gordon, where the power station is located.

“I took out a big ad in The Australian, it was over $1,000 at the time, saying Lake Pedder is another disaster for Tasmania… It was sort of a cry in the dark but it also alerted the Lake Pedder campaigners to the fact that this unusual doctor had arrived in Launceston, and I quickly got asked to stand for Parliament. I didn’t want to, but I did.”

The newly formed United Tasmania Group (UTG) is acknowledged as the world’s first environmental political party to contest elections. The party was formed during a meeting of the Lake Pedder Action Committee to field candidates in the April 1972 Tasmanian election. The founder of the UTG, a senior lecturer in botany at the University of Tasmania, Dick Jones, asked Bob to stand, as they needed a candidate in the north of the state.

“I stood with him on a Senate ticket, I think I got 112 votes statewide. But I quickly learned that environmentalism is off the agenda in politics, even more so back then… This was a period of nascent organic farming, permaculture, a lot of things happening in Tasmania, and it was all viewed with disdain and arrogance by the Hydro-Electric Commission, which had no trouble running ads against the UTG to say our policies would lead to higher power prices and the loss of jobs and so on. So we learned from that for the Franklin campaign, which came a decade later.”

Wild “from source to mouth”, the Franklin River is in Lutruwita’s southwest, and the Hydro-Electric Commission coveted it to create another hydro-electric dam. Bob gathered a group of activists in his home — all of whom were either members of the UTG or had campaigned for Lake Pedder — to discuss the Franklin’s protection, and together they formed the Tasmanian Wilderness Society (TWS).

“We discussed peaceful direct action. Some of the group had considered it but had decided against it because they didn’t want to lose public support by sitting in front of bulldozers. But we invited some Quaker activists from New Zealand to talk to us about the theory of direct action and communal direct action, and while some individuals amongst us hated it, it nevertheless was enormously important in the blockade that saved the Franklin River.”

The TWS coordinated the massive campaign against the Franklin Dam, which lasted seven years from 1976 through to 1983. The campaign was initiated by a film that screened on Tasmanian television stations, and was followed with blockades on the Gordon and Franklin Rivers, many public rallies, letter writing, widespread door-knocking and significant political actions. In 1980, 10,000 people protested on the streets of Hobart — more than three times the size of any public rally to that moment in Lutruwita — demanding the wild Franklin be saved. Through the strength of the campaign, the Tasmanian government backed down on its initial plans for a new site for the dam, but the Wilderness Society did not back down from its call for “NO DAMS” in the southwest of Lutruwita. Their stance was supported by the uncovering of cultural artefacts at Kutikina Cave, located on the Franklin River, which led to the creation of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area in 1982, strengthening the position of TWS and the protestors. After a deadlock in the Tasmanian Parliament and an eventual referendum, the sitting Labor government was defeated in a state election.

“It was then that the strong man of Liberal politics arrived on the scene, Robin Grey, he won the election over Labor in 1982. In every seat of that election we stood ‘Save the Franklin’ candidates, and in every seat they lost. Although Norm Sanders here in Hobart, in Denison, had been an advocate for the Franklin’s protection, he was, to my knowledge, the first environmentalist elected into a parliament anywhere in Australia, he was a trailblazer. But he resigned his seat in Parliament because of the mistreatment of the Franklin Blockaders that got tougher and nastier as time went on, it was a very clear the government was calling for harsher treatment.”

Bob was one of 1500 people who were arrested during the Franklin campaign and was one of 600 jailed, when he spent 19 days in Hobart’s Risdon Prison.

“The day after I came out of jail, I was elected to Tasmania’s House of Assembly on a countback. So I was suddenly in Parliament on the side of the Franklin ticket, while also being director of the Wilderness Society, helping to run the blockade that was happening on the Gordon and Franklin Rivers. But I said at the time when the Franklin is saved, that’ll be my political career.”

Through the support of the newly elected Prime Minister Bob Hawke — who had promised to save the Franklin in the lead up to the election — and intervention from Australia’s High Court, construction of the dam was stopped and the River was saved, yet Bob Brown remained in politics.

“We had parallel campaigns to stop wood chipping and the marauding of Tasmania’s forests, and it was accelerating at a great rate, and there were social justice issues that I wanted to attend to, because nobody else in the Parliament was giving them voice, so I stayed on.”

He stayed for ten years. During his tenure, Bob proposed legislative initiatives on gay rights, nuclear regulation and euthanasia (amongst others).

“In the 1989 election, we ended up with five Greens seats that allowed us to double the size of the World Heritage area and to get new National Parks. You could say I became a relentless driver for the environment, but to me it was just about relentless common sense, it was a priority that looked to the future. And in retrospect, I would have regretted greatly backing off when that opportunity arose. But after ten years, I’d had enough, so I resigned from the Greens and took three years out.”

Bob went on holiday, travelling the world until he was pulled back to land he loved. He was drawn back to politics, initially to campaign for the newly created Australian Greens, and eventually standing for election in the Federal Senate in 1996 with the provision that he could continue to be an activist.

“It included, if necessary, breaking the law, even though under the Constitution that loses you a seat in Parliament, and the Greens were happy to accept that condition.”

He was the first Greens’ candidate to be elected to the Australian Senate.

“When I arrived in Tasmania and found this nascent Greens Party, I felt at home with their politics that was based on a humility for nature and a concern for all human beings, and that includes all human cultures. So taking that on and helping to develop it was important. Labor will always grab kudos for social justice, Liberals will always grab kudos for economic innovation, but what they don’t have is any kudos on the environment, except when it’s manufactured here and there, and so the Greens Party grew.”

Bob Brown was a sensible voice in the Senate, often opposing the conservative Liberal government of John Howard. He introduced bills to block radioactive waste dumping and to ban mandatory sentencing of Aboriginal children, he was vocal of Australia’s involvement in the 2003 invasion of Iraq and he famously told John Howard to “relax and accept gay marriages as part of the future’s social fabric“. When four Greens senators were elected in 2004, Bob was formally named the first Federal Parliamentary Leader of the party. In 2007, he stated that coal was the energy industry’s “heroin habit” and suggested the ban of coal exports. He said it was an “appalling and disgusting failure” when Kevin Rudd failed to commit to strong carbon reduction targets in 2008. He also suggested tax revenues from the excess profits of the coal industry should be set aside for future environmental catastrophes in Australia.

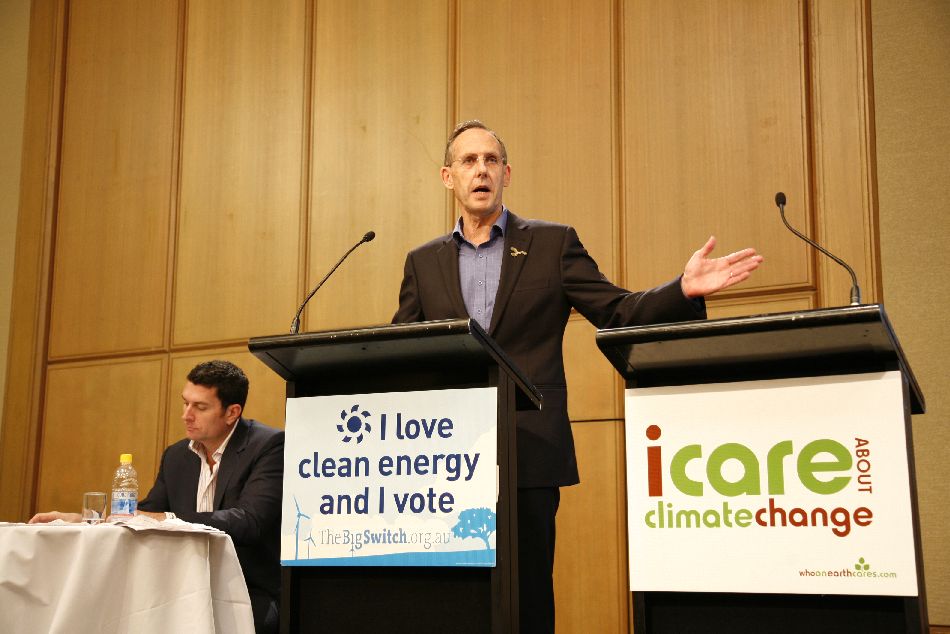

In the 2010 election, the Greens achieved a historic result attracting 1.6 million votes, with the election of nine senators and one member of the House of Representatives. It meant that the Green held the balance of power in the Senate and Bob used this position to negotiate.

“We brought in probably the most advanced climate change legislation, of regulation and offsetting. We got it through with Julia Gillard as Prime Minister because we drove a very hard bargain. You might remember she’d said four days before the election, there’ll be no carbon tax under a government that she runs. Well 18 months later, they not only had a carbon trading scheme, but one of the best in the world.”

In April 2012 Bob stepped down as leader of the Australian Greens and then he retired from the Senate in June 2012. This time he stepped away from politics for good.

“I endlessly quote Abraham Lincoln in 1857 saying that the corporations are coming to steal the throne of democracy from the people, and it happened. I watched our democracy become usurped by the wealthy and the corporate sector. That influence spreads right across the spectrum and there’s no greater example of that than the Murdoch ownership of the media here in Australia, which is corrupt and perverting of democracy. But one thing they all have great difficulty with is peaceful activism, and history shows that to be the case.

“I had seen that through the Pedder and Franklin campaigns, and our forestry campaigns — which I continued to be involved with while I was in politics — but a large component of the environment movement, which I love dearly, was trying to influence politicians by going to see them. I was very well aware they are no match for the corporate lobbyists who infested our parliaments, banging on people’s doors every day, particularly ministers doors, leading to this absurd situation we have now where 80% of Australians want native forest logging stopped and 80% of politicians want to subsidise it with even more public money. So getting out and focusing on activism was important, because politics doesn’t know how to deal with it. It cuts through.”

Along with Steven Chaffer, Bob decided to form an organisation with activism as its focus.

“I was in my late 60s and I recognised that it was a big thing to take on, but I had people like Steven. We started with nothing except a good idea, but we knew we had a lot of public sympathy out there.”

Their first employee was Jenny Weber. Jenny had grown up on Dharawal Country in Wollongong and experienced a lot of her childhood at the beach.

“I had this sense of awe about the ocean being bigger than I am, and the need to be careful in the ocean, it’s not something I took for granted, I had to learn to swim with the waves pummelling in. I was totally immersed in nature as a child.”

Jenny also grew up with the political leanings of her father, who was a member of the Australian Labor Party. He was also a teacher and part of a union.

“He was an organiser. I have memories faintly of my Dad organising or the teachers going on strike or always handing out how to vote cards on voting day. So really early on I was aware there was something going on with politics, to the extent there were politicians that for some reason were on the bad list. There was always a conversation about politics in my life, which was really influential in my childhood.”

She liked punk music and helped organise concerts of visiting international bands at the local youth centre.

“I think we were like 14, 15. It was a fabulous life, and it introduced me to a DIY style of working and giving back to your community, and it set the groundwork for the belief that if you want to get stuff done, you just need to get a few people to get together and do it.”

At 17 she met her current partner, Adam, who was involved with the Wilderness Society and opened Jenny’s eyes to activism and the possibility of dedicating her life to the environment. Adam was living on Bundjalung Country near Byron Bay and took Jenny to a logging area in the Whian Whian State Forest when she was 18.

“I just could not believe it. And then I met the North East Forest Alliance, who were a bunch of activists pulling off blockades. It was a whole new thing, I was like who is this community of people who are getting together to resist the destruction of the environment? So I just immersed myself into that space entirely.”

Jenny was about to complete her university studies when Adam said to her, “I’m going to Tasmania, do you want to come? I was like, ‘not really, there’s no live music, I can’t swim in the sea. I thought that it would be freezing cold all the time. And then he was like, ‘I’m going to go anyway.’ So I had to choose between doing whatever I might have ended up doing in New South Wales and coming here to Tasmania, so I asked, ‘can we do a deal that it’s just for six months?’”

They drew a circle on a map between Hobart and the southern forests and they decided to move to Huonville.

“It’s a logging town in the middle of nowhere, we didn’t know anyone, it was a completely bizarre thing to do.”

They initially volunteered with the Wilderness Society in Hobart, but Adam was inspired by his time with the Byron Environment Centre and the North East Forest Alliance and was keen on creating something similar in the southern forests of Lutruwita.

“We set up this little place called the Huon Valley Environment Centre, which became our life for about 15 years. Being a forest activist, taking action, doing lots of blockading and forest protests. We had two beautiful children, we were living off-grid on 60 acres of wildlife reserve in a straw bale place we built, and we were there resisting non-violently in a town that hated us, being right there with the logging community.”

Jenny and Adam were living on the frontlines.

“I was shopping once with my little ones in Woolworths, and this woman just screamed at me and was like, ‘I’m going to lock-on to your trolley, that’s what you do to my husband,’ and it was a bit shocking. The same thing happened at the laundromat, people getting angry at me. I think it’s just being calm and trying to state your place or ignoring the situation completely. In the laundromat, the woman was a bit more aggressive and so I just tried to de-escalate and say, ‘look I’m just here for the forests.’ I also had a death threat against me. They said, ‘I saw her on the street, I should have run her down, I’m going to kill that bitch.’ So I went to the police, and the police handled it okay. But I never truly feared for my life. I’ve spent a bit of time in Sarawak, we have a company here in Tasmania that’s from Sarawak, and it opened up my life to the indigenous people there fighting for their forests, and my time with them made me realise I’m a white, privileged, educated woman who lives in a democracy, and I am so far from being threatened in my life because of what I do. So I’ve had a reality check a number of times.”

In 2012, the Tasmanian government struck a supposed peace deal with environmentalists and the logging industry, the Tasmanian Forest Agreement.

“We didn’t agree with the deal, it compensated this Sarawak logging company to stay in Tasmania. And this was after we had achieved some great gains in the Japanese markets, and Ta Ann was going to leave Tasmania, and these environmentalists went into those markets and said, ‘no, keep buying from Tasmania, don’t leave,’ which was shocking, and so we lost, a lot of activists were disillusioned, they felt they had been sold out. We had a beautiful community of people who were all volunteers and hanging on by a thread. It wasn’t like they had paid employment, they were all dedicating their lives to the forests. And I witnessed when you have a tipping point like that, where you feel sold out or disillusioned, that’s all that needs to happen and it’s over. Why would I give my life up if I’m not going to be, you know, effective?

“So at that time I was really frustrated because not only did we have success and gains in unsettling a major company, we also had environmentalists who were working against us. Anyway, I saw Bob at an art exhibition in town. We used to run these art exhibitions where the activists would tell their stories through art and they were beautiful and confronting and intense. And so we had an exhibition and Bob came along and he asked about the Centre closing and I was like, ‘I’m so angry, I’m going to leave Tasmania, Adam and I are just done, we’ve had enough.’ And he said, ‘if you’re angry and you haven’t been angry until now, imagine what you could do if you keep campaigning, why don’t you come and work for the Bob Brown Foundation?’ And I was blessed in that very moment of my life, I had a blessing that people would love to have across this planet, to have Bob Brown take me under his wing and say, ‘let’s campaign together.’”

Tony Abbott had just become Australia’s Prime Minister, and he wanted to remove Lutruwita’s forests from their World Heritage listing.

“Insane. So my first task here was to resist that and say, ‘no way.’ Incredibly it meant I went to Doha to the World Heritage meeting and was part of a team of people who were lobbying to not have the forests delisted. I thought I was just here at the Foundation for that little stint to make sure Abbott didn’t get his way. And we were successful, there was no appetite in the World Heritage Committee for that to happen. And when I returned, Bob said to me, ‘okay, now there’s a window of opportunity to have the Tarkine protected, so let’s dedicate you to the Tarkine campaign.’ Bob had been trying to get the place protected for 20 years, but it’s just so powerfully dominated by the mining industry and a little bit by the logging industry. So I was like, ‘yeah I’ll stick around with the Foundation.’”

There are now around 20 employees at the Bob Brown Foundation, supported by a dedicated community of volunteers whose activities include sending out merchandise, gathering petition signatures or, if they’re involved in frontline demonstrations, they might be locking-on to a tripod or in a tree sitting.

Dr Colette Harmsen has been a consistent presence at the Foundation’s many protests and blockades. Colette was born and raised in Lutruwita to a Tasmanian mother and a Dutch father. They lived in the bush, so Colette lived a “sheltered and isolated” life immersed in the surrounding natural environment.

“As long as I can remember I was into insects and plants. I spent hours watching ants, building nests and doing that kind of stuff. I used to smear honey on the walls in my bedroom so the ants would come in and eat it. It’s funny, I haven’t seen that species of ant since I was a little kid, the insects seem to be diminishing.”

Her parents were part of the activist community of the time, attending protests all over Lutruwita, so it seemed normal to want to protect nature, “like it was normal that you didn’t want people to come out and kill the animals or pollute or destroy.” Colette eventually moved to Yuggera Country, to Brisbane to study veterinary science, but returned to her homeland to join the Save the Tasmanian Devil Program, where she worked for eight years.

“My job was as a field veterinary officer, so I had a pretty good time of it working with the program, which felt worthwhile up to a point when I realised I needed to step up again, like just going to protests didn’t feel like it was enough. So I started locking-on to stuff. I think the first time I was arrested I didn’t even lock-on to anything, I think I stood with a group of other activists and we stood in front of a primary school and refused to leave. They were having a meeting inside about the pulp mill, politicians and local people and councillors, and we all got arrested.“

Since then Colette has been arrested 23 times.

“Most of those times I have been chained to things like machinery gates, drill rigs, that kind of thing. I was up a tripod at one stage. When I do that I feel that it doesn’t matter what people say, I’m there and I’m not going anywhere, and they’ve got to physically come and cut me off and remove me, and if that doesn’t make people go, ‘why are people doing this, this doesn’t make sense,’ then I don’t know what will.

“I guess the reality is that people don’t pay much attention, but the more we do it, I can see it’s making a difference, every step of the way it is making people ask ‘why are they arresting these people for? Like they’re trying to protect the planet,’ and at some point, someone’s going to make a decision and just say we need better environmental laws or we need better protection of forests.”

Having lived in Lutruwita for most of her life, Colette has seen firsthand how the forests are constantly threatened with destruction.

“The first time I flew to Melaleuca, which is in the southwest of Tasmania, to do a walking trip, we flew south from Cambridge Airport and we flew over Hartz Mountain and a lot of the southern forests and out towards the southwest wilderness. And when I looked down from the plane in the southern forests area, I could see a patchwork quilt underneath you: it was all the forests that were being logged and then regrowing at different stages. And basically Forestry Tasmania has all the forests available to them that aren’t in the Southwest Conservation Area or the National Parks, and all of that is just a patchwork of logged areas that are regrowing at different ages. And it’s devastating that we go in there to save one little patch, and it’s like the last old growth patch in the whole bloody area, and everything else is a bunch of plantation trees. And it just really hurts me to think that all of that would have been a continuous forest of absolutely pristine mosses and fungi and all the wildlife living in there, but now it has been chopped up into tiny pieces.”

It’s the loss of this natural heritage that pains Bob too.

“People need to recognise that the planet is finite, and that it’s amazingly intricate in the way in which it has evolved and supports life. There is a spiritual dimension to that, which I often shortcut for people by saying if you give a person a bunch of flowers, which is from wild nature, they feel good about it, but if you give them a bunch of plastic flowers, which look exactly the same — because they’re amazingly contrived these days — as they slowly realise they’re not real, it’s often a sign of insult. Why is that? You could write books and books and books on it, but it’s because we are creatures of the forest and the wild planet, and that’s where our soul as well as our body comes from, and we’re still linked to it, but we’re divorcing ourselves artificially, or cutting ourselves from it and destroying it at a great rate.

“As a boy, there was a book called ‘The Big Snake Hunters’ that came out of England about the Amazon, and while it was the typical beagle stuff of those days, I was nevertheless imbued by this idea, which was then still true, that there were large realms of forest that we from the developing and invading world didn’t know about, and people lived in all of them and were completely encompassed in body and mind by them. That’s almost gone in my lifetime. And when I hear from the World Wildlife Fund that 70% of the mass of wildlife has gone since 1970, or the other statistic that 94% of the mammals left on the planet are human beings and what we eat, and 6% is wildlife, you get a picture of the complete desecration of the planet.

“The thing about it is, while more and more people are becoming alarmed about it, it’s increasing in rate. And when you talk about a road going through the Amazon or the felling of ancient trees here, it’s all part of this onrush of materialism, capitalism if you like, which is quite absurd. It’s working in a finite system, which is the planet, and yet there’s not a government that I know of that doesn’t adhere to growth as being a central pillar of good management. And growth means increased exploitation of nature in a world in which we’re already using twice the renewable living resources of the planet. So every morning we wake up to fewer forests, fewer fisheries, less arable land, fewer species, more human mouths to feed, and generally more devastation and anxiety.”

These words relate back to pre-colonial days, when Tasmania was always referred to as Lutruwita, and the island was populated by Palawa people and was covered in the world’s tallest flowering plants. But it wasn’t just Lutruwita, it was all over the land called Australia that was covered in its native vegetation and teeming with ancient wildlife coexisting with the diverse and vibrant cultures of the continent’s Original Peoples. Can we ever know how much has been lost now that so much is gone? To paraphrase the Revolutionary Proclamation of the Junta Tuitiva, most of humanity maintains a silence that closely resembles stupidity. But fortunately there are still giants like Colette, Jenny and of course the great Bob Brown, who protect the giants of our ancient past so they will still remain as part of our future.

“We are so fortunate in this country but it is so easy to be complacent. I learned early on that we’re just passing patterns here, all species are a relay of life, and we’re part of a community. Capitalism, of course, makes the individual all important, but as human beings, we’ve always lived as communities, with the spirits of ancestors before us and the hopes of future generations in front of us. And it is incredibly important to honour those past ancestors, but to also be active, to put ourselves on the line for those coming after us, who can’t come back and undo what’s happening now.

“Although the idea that there is no time, that we can do nothing else but be planet savers, can be self-defeating. It’s important that people find good companionship, have good relationships, have parties, have holidays, complete their studies and assume that there is time. You have to take time. And it’s very, very important for people to look after themselves. The idea that you can have fun in such a desperate and daunting planet seems contra intelligent, but nevertheless we are just human creatures, we do like happiness, and we have to find that in amongst this very fraught life we’re leading, waking the planet up and converting it against all odds into a global community that, above all, respects the planet and life on it and works to ensure that it’s here forever.”

As they say in parliament: hear, hear!

Anton Rivette is a writer and photographer. He leads storytelling at eco-nnect.